Snows rode the stiff, unseasonably warm March wind north, skein after skein streaming overhead–each containing hundreds, sometimes thousands of geese.

At times, the line of flocks stretched from one horizon to the next. Flat on our backs in a southwest Iowa stubble field, we greeted the grand passage of white geese with flags and the raucous barking of two electronic callers.

Behind us sprawled a collection of 1,000 decoys, rags, silhouettes, and shells. Situated in a cornfield with the Nishnabotna River on one side, a duck club impoundment on the other, our best turkey decoys occupied a tempting spot where tired, hungry birds could find both food and a roost.

The flocks spilled air as they passed over us, dropping, flipping sideways to plummet for an instant, then righting themselves and wheeling around into the wind, coming in low with a thousand eyes peeled to examine our spread.

Every flock, it seemed, followed an invisible trail in the air left by the birds that had preceded them; 40 or 50 yards out they’d start a cautious slide to the left, skirting the edge of the spread instead of committing.

That’s when we’d call the shot, plucking a few birds from the edge of the flock as the main body flared out of range.

Occasionally a single would parachute straight down into the spread, and we’d add it to the pile of geese hidden under the shells.

What Tips Did We Use to Achieve this Feat?

Merely being underneath the spectacle of hundreds of thousands of snows and blues following their ancient urge to fly north fills your inner bird watcher with awe.

It’s reason enough to be in the field in late winter in the Midwest as the lesser snows journey back to their tundra breeding grounds.

With them come ducks, in the full glory of their spring plumage, and bald eagles looking for a straggler to make into a meal.

Yet, the waterfowler in you hungers for more than the sights and sounds of the spring migration–punctuated by scratch shots at flocks that come close but don’t quite commit and a few suicide singles. You want to see 1,000 geese throw caution to the winds and pile into the landing zone.

|

Movement is critical to a realistic spread, so in addition to socks and motion decoys, flagging is often the cue that convinces geese to drop down for a visit.

|

A huge spread pulls snows in for a look, but it takes more than numbers to lure wary flocks the last few yards that make the difference between shooting a few on the swing and raining geese into the decoys.

Skills & Finesse

Successful spring snow goose hunting requires skill, finesse, hard work and attention to detail. John Vaca of Liberty, Missouri, is one hunter who’s become serious about the art and science of fooling spring snows.

Vaca lives and hunts in the neck of the funnel along the Missouri River where birds travel on their way north in late February and early March.

Like me and my friends, he’s hunted late winter/spring snow geese since the special season and the conservation order designed to reduce overpopulated mid-continent snows began in 1996. A dedicated waterfowler and Pradco pro staffer, Vaca has made a study of hunting northbound snows, and he’s seen his success rate rise with each passing year.

“Some days we run out of shells. We’ve had 100 birds on the ground by 9 a.m.,” he says. “Then there are days when we’re lucky to shoot 25 in a long morning. I still have days when we bag one or two and are lucky to get them.

If it was easy every day, I wouldn’t like it so much. I have a lot respect for snow geese. They’re cagey, and the big flocks have so many eyes you have to be twice as well hidden and twice as convincing.”

By and large, Vaca believes hunting northbound birds is slightly easier than fooling them during the fall. “The geese are in bigger flocks and seem to decoy well because they aren’t as pressured as they are in the fall,” he says. “There aren’t as many people out, so the birds feel comfortable resting and feeding in an area until they’re ready to go north again.”

Nevertheless, Vaca says there’s more to hunting spring snows than simply putting a lot of white decoys on the ground.

“You have to keep ahead of the geese,” he says.

“I see more people every year out lengthening their waterfowl season, doing what they like best. Some of them are learning how to be successful; others keep right on doing it wrong, blaring their electronic callers. They may scratch out three or four out of a flock and educate the other 2,000.”

Windshield Time

As with any goose hunting, spring snow hunting begins with what Vaca calls “windshield time”: driving the back roads to find concentrations of feeding birds.

Like most serious goose hunters, Vaca leaves birds alone on the water and hunts them in the fields; given a safe refuge on the roost, geese will stay in an area longer.

Some days birds fly only a short distance to feed. Other days they may travel for miles before setting down.

The only answer is patience, a full tank of gas and good binoculars; finding a field where birds are actually feeding is a key to success.

Usually, birds will leave the roost and fly upwind so they’ll have the wind under their tails on the return flight, but there are no set rules in goose scouting except one: Put in your time.

|

“I have gone out on a flyway, set up a spread and short-stopped birds on their way somewhere else, but it’s always better to be where the geese want to land,” says Vaca.

If Vaca finds birds feeding in a field in the afternoon, he’ll plan to return in the morning. Merely finding the right field, however, isn’t enough.

Vaca will study the lay of the land carefully, trying to mark the exact location where the birds are feeding and picking out landmarks he’ll be able to use to find his way to the X in the dark the next day.

Finally, he looks at the birds themselves. “I don’t believe in setting out decoys in J’s or W’s or fish-hook patterns,” he says. “I want to mimic the geese in the field as exactly as I can.”

Next morning, Vaca will return to the field, often with eight or nine friends in tow to help set out decoys under the glow of the headlights.

“We put out 1,500 to 3,000 rags and silhouettes, about 90 percent white decoys and 10 percent blues,” he says. “If you have a lot of people, you can actually get set up in an hour or so.”

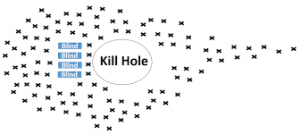

He’s careful to make several landing holes in the spread; like any other waterfowl, snows don’t want to land on top of birds on the ground but look for an opening in the flock.

He positions his blinds near the landing holes. While snow goose hunters traditionally wear white smocks and become decoys themselves, Vaca prefers to have his hunters wear camo and cover-up in low-profile ground blinds–especially hay-bale types.

|

Sometimes it pays to move blinds away from the decoys and place them downwind where flocks will pass close by and within shotgun range as they swing around a spread. When the birds are playing coy, it’s one of the best ways to shoot a few.

|

“The geese see hay bales all the time and don’t associate them with danger,” says Vaca. “It doesn’t seem to matter whether there are bales in the field already or not. The nice thing about the hay-bale blinds is that you can sit up inside them comfortably and stand up to shoot.”

Once the decoys are out and the blinds are situated near the landing holes, Vaca is always ready to rearrange the setup if conditions warrant. If the geese seem to prefer one landing hole over the others, he’ll rotate shooters into the hot corner or move all the blinds into range of the part of the spread the birds want to use. If geese are landing short of the spread or in an unanticipated spot, he’ll move some of the decoys into that area as blockers, forcing the birds to land elsewhere.

Finally, on those days geese don’t want to finish, he may take all the blinds and move them 60 to 100 yards downwind of the decoys. “Snow geese will work sometimes but not finish,” he explains. “They’ll come in, look at the decoys, then slide around the spread. We move the blinds so we’re right underneath them. Then we get easy shots when they’re low and looking at the spread. The decoys always attract geese, but you don’t always kill geese in the decoys.”

While sheer numbers of decoys matter a great deal in snow goose hunting, Vaca also believes motion in the spread is critical to success. Texas rags, tied as windsocks, waddle like feeding geese in the breeze. T-flags help create lifelike motion as well.

|

Last season, Vaca began using CarryLite’s new Extra Motion Lander with his rotating-wing decoys. The Lander consists of an arm attached to a string controlled from the blind. Pulling on the cord raises the bird up and activates a mercury switch that turns the decoy on. It creates the illusion of a goose landing or getting up and swapping places in the field.

Finally, although electronic callers–now legal in special late seasons–have boosted success, Vaca says there’s more to using them than simply switching the caller on a top volume. “We’ve had a lot of success with electronic callers, but you have to learn how to use them,” he says. “I like two–one on the right side of the decoys and one on the left. On real windy days you may need to leave them on at full blast until the birds land, but most of the time I like to feather the volume down as the geese approach for a more natural sound.”

Vaca often shuts off the caller altogether as geese come within 200 yards and switches to a traditional reed-style mouth caller. “The key is to get everyone in the group calling. It doesn’t sound right if there are 3,000 decoys on the ground and only one goose calling. The more, the merrier.”

Whether hunting can eventually stem the white tide overwhelming the tundra breeding grounds remains to be seen. Liberalized regulations, electronic callers and unplugged shotguns give us the tools we need to increase harvests, but the average snow goose is

11 years old and has seen it all several times over. We need to hunt smarter to fool them.alloutprodux.com